- PRODUCTS

- Security Platform

- BioStar X | On-Prem SecurityNEW

- BioStar Air | Cloud Security

- BioStar 2

- Access Control

- Access Control Unit

- Biometric Readers

- RFID Readers

- Mobile Credential

- Peripherals

- Wireless Door Locks

- SOLUTIONS

- SUPPORT

- ABOUT

- device_hubHUB

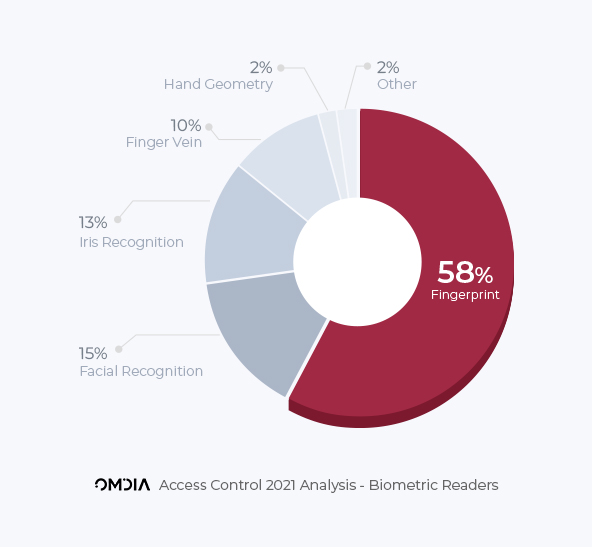

According to security research firm OMDIA, in 2021 fingerprint readers accounted for nearly 60% of all biometric readers for access control.

But most people don’t need hard numbers to guess that fingerprint readers, sometimes called fingerprint scanners, are more popular than other biometric access control options like facial authentication or iris scanners. Fingerprint door locks and time and attendance systems have become common fixtures at workplaces ranging from construction sites to grocery stores to data centers.

Convenience, flexibility, and easy integration with time and attendance systems all play a role in making fingerprint readers so popular, but it’s their accuracy and security that make fingerprint biometrics the default choice for most businesses.

In this article we will take a look at the technologies that make fingerprint readers for access control so reliably secure.

How to Read a Finger (and Make Sure it’s Real)

Fingerprint readers come in two basic flavors, optical and capacitive. As the name suggests, optical fingerprint readers use light and an image sensor to scan fingers, while capacitive fingerprint readers use an array of pixels to read tiny variations in electric charge in the ridges of a fingerprint.

Until recently security pundits were nearly universal in proclaiming that capacitive readers were more secure, as they were difficult to spoof with fake (or dead) fingers. Google will happily serve up a buffet of these outdated opinions.

Recently, however, engineers have significantly improved optical fingerprint readers with innovations such as Suprema’s Dual Light Source Imaging and Live Finger Detection deep learning algorithm, as well as hybrid readers that combine the best elements of optical readers (speed and accuracy under a wide variety of conditions) with the best of capacitive readers (foolproof).

A Template, Not an Image

The first step in using a fingerprint reader is enrollment – the initial scan of a person’s fingerprint, which will be stored in a secure database. But contrary to what crime dramas show, what’s stored in the database is not an image of the fingerprint. Instead the reader or scanner stores a mathematical biometric template that maps out a fingerprint’s ridges, valleys, deltas, loops, and whorls. This has several advantages.

First, it’s more secure. A hacker, no matter how skilled, cannot steal an image of your actual fingerprint if it isn’t stored in the database. Second, it makes matching fingerprints fast. Usually less than 600 ms.

Finally, fingerprint templates only take up about 384 bytes meaning you can easily store hundreds of thousands on a standalone reader. Storing images would take 100 times as much memory.

Matching 1 Fingerprint in 100,000

Companies generally use fingerprint access control in one of two ways. The most common is as a single form of authentication. Walk up to the door. Touch the fingerprint scanner. If your fingerprint is in the database, the door unlocks.

The second method, preferred by highly secure facilities like data centers, is two-factor authentication. First you tap an RFID or mobile access card, then you touch the fingerprint reader to prove you are the owner of the card.

The first method relies on 1:N matching. The fingerprint reader has a database of authorized users and does not know who will touch the reader at any given time. In less than a second it must recognize the fingerprint, create an ad hoc template, and compare that template against potentially tens of thousands already in the database to determine if the finger’s owner is authorized to enter.

The second method relies on 1:1 matching. The reader already knows whose finger it should recognize, based on the access card. This process is less computationally intense, and typically a bit faster, but less convenient, as people must remember their cards and go through a two-step process.

Balancing Accuracy with Security (FRR and FAR)

When IT infrastructure teams, facility mangers, or business owners are considering fingerprint biometrics as part of an access control system, one of the most common questions is, “How likely is it that an unauthorized person will get access?”

This brings up the topic of False Rejection Rate (FRR) and False Acceptance Rate (FAR). FRR means that an authorized person’s fingerprint is rejected. This isn’t so scary. If at first you don’t succeed, try again. FAR means that an unauthorized person can gain entry (or check in for someone else at work using a time and attendance system). As you can imagine fingerprint biometrics companies work extremely hard to reduce the False Acceptance Rate.

Many factors contribute to the FAR including the quality of the sensor, the quality of the algorithms, and system settings and enrollment numbers.

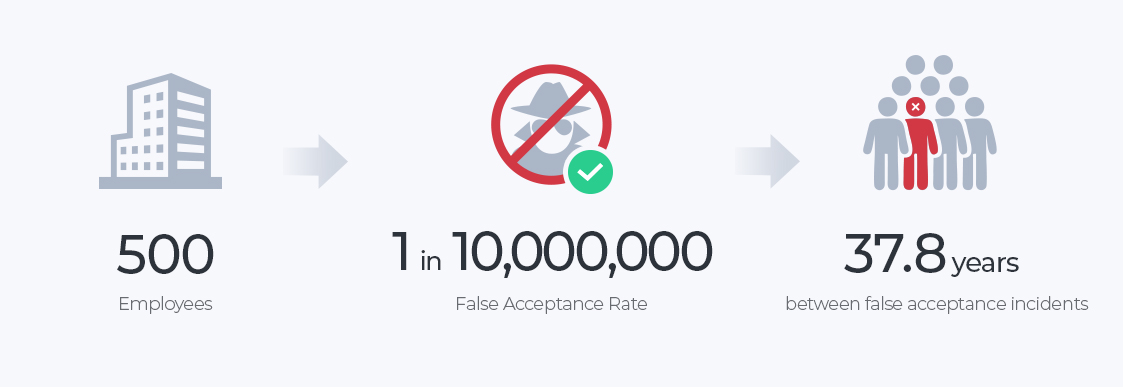

Suprema’s fingerprint readers have three sensitivity settings: Normal, Secure, and More Secure. When set to the highest sensitivity, with 500 employees enrolled, the real world FAR will be less than 1 in 10,000,000. To put that in real terms, if each of the 500 employees touches the fingerprint reader twice-a-day, every workday of the year, on average a company would have one false acceptance every 37.8 years.

Considering their security, convenience, and ease of use, it’s clear why fingerprint readers have become such a popular choice for biometric access control. There are no cards to lose, steal, lend out, or leave at home. Just touch the fingerprint scanner and in a fraction of a second, the door opens. If you are curious to learn more about biometric fingerprint readers and access control systems, read the other articles in this series, or contact our sales team.

Explore Our Products